Whoever he or she is, your main character has to be someone your reader can identify with. If he’s the hero, they need to like him and empathise with him throughout the story. If your protagonist doesn’t grab your reader from the start, you’ve lost the plot.

BY GINNY SWART

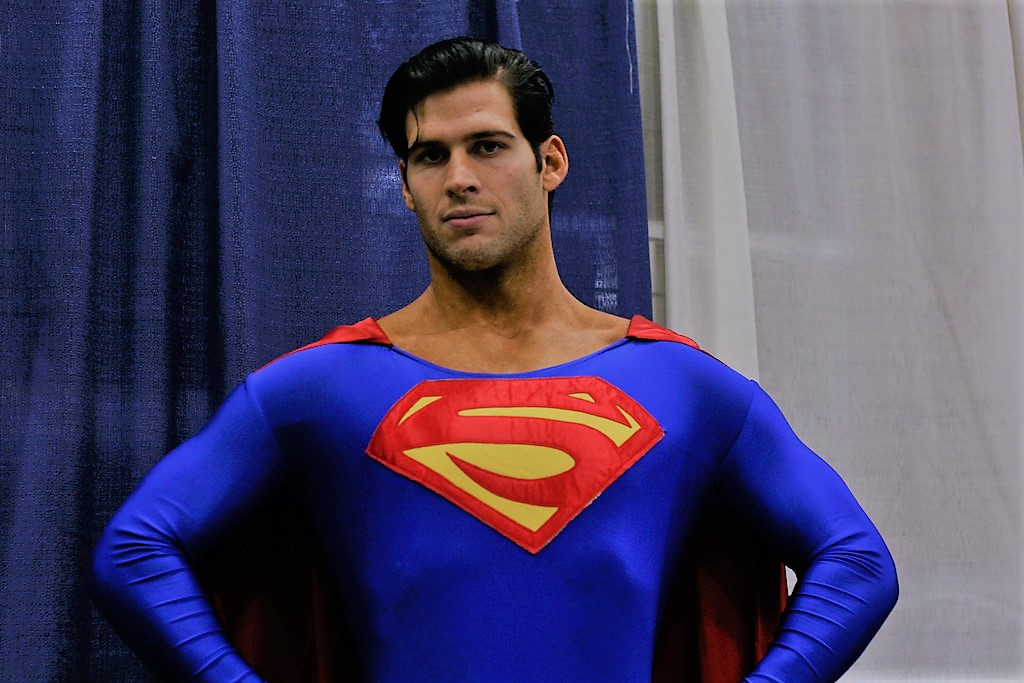

Let’s say you have a great plot in mind with a strong central character, Greg. Greg is a doctor. You describe him as good looking, with a subtle sense of humour, loving his mother and being kind to animals.

Your reader can’t fail to love him too, right? Wrong. You might think you have presented Greg as every woman’s dream, but perfection is boring.

1. Everyone has flaws. So should your heroes.

This character, Greg, needs a few flaws to make him real. Flaws create conflict, which makes your whole story more interesting and your readers will identify with him more easily. Nobody is all good, or all bad.

So, while it is essential that your reader likes your protagonist, and he needs to have mostly admirable characteristics, small things, like a quick temper, forgetfulness, untidiness or an insatiable appetite for Belgian chocolate won’t detract from his innate suitability as a hero. A few irritating habits will complete the picture of a real man.

If he’s the villain, you can’t paint him as totally rotten and villainous. He might be a ruthless corporate raider or a serial killer but he needs to love his dog, make his own bread or be a keen bird-watcher to make him believable to your reader.

Let’s say Doctor Greg’s gorgeous tanned face has a small white scar to mar his beauty. How did he get it? Has he got an uncontrollable temper that got him into a fight long ago and is he still struggling to control this weakness? He might be a doctor these days, but let the reader discover his interesting past which might affect his present behaviour. And a good outburst of temper is always a good peak in any story.

2. What does he look like?

Part of characterization is describing someone’s appearance. Readers need a few hints, but they like to form their own picture, so don’t give them a full-length portrait.

Try a few revealing details instead.

“Michael ran his hand through his thinning grey hair, adjusted his horn-rimmed glasses, and gave her a severe, owl-like look.”

or

“Jenny adjusted her skirt in the mirror, pleased with her new reflection. Copper highlights and spiky heels pushed her scarlet mini to another level of wicked.”

Appearance can also be hinted at with dialogue. For example:

“Great new shoes, Jean. You’re so lucky you can wear those high heels.”

“Well if I didn’t they wouldn’t let me into the pub,” she grinned. “It’s bad enough being mistaken for a fourteen-year-old boy every time I wear jeans.”

3. How does he speak?

It’s important to let your protagonist speak in character. If you describe someone as coming from the country, his conversation is not likely to sparkle with sophisticated wit.

Also, what he talks about helps build the picture of him – the price of a new Beamer? The excitement of share trading? The deplorable state of education?

If you’re building a picture of a young mother, she’ll talk about children, or shopping, or moan about her husband. She’s not going to talk about pension schemes and arthritis. (This might sound a bit stereotyped but in 1500 words you don’t have the space to make someone too quirky.)

If you’re writing about children or teenagers, make their dialogue realistic. Make sure you use the latest catch phrases. Cool and wicked are still okay, fab and bad (for good) are not.

4. Write your backstories

Sometimes you’ll read about lucky writers who claim “the story just wrote itself”. This is because the writer had a really good idea where all her characters came from before she started writing. She knew what they looked like, she’d made notes about their back story (i.e. what had happened to them before the story started). She knew what sort of opinions they’d hold and if they were fast-acting or slow, deliberate thinkers. So when the author put them into a difficult situation, it was easy to work out how they’d react and what they’d say.

It’s worth spending a lot of time shaping your characters. They are almost more important than the story itself. Once you’ve got your main characters and their back-story fixed in your mind, start writing. You may find you too are one of those lucky writers whose characters just write the story for you.

Copyright, Ginny Swart, All Rights Reserved

About the Author

Photo credit: Flickr.com/Lore Sjoberg